Goal

Understand what a meter is and what it means. To be able to identify basic meters.

Meters

Time signatures told us what note gets the beat and how many notes go into a beat but what time signature did not tell us is how to stress the beats. This is the job of meter.

Say we have a measure of 4/4. The most basic way to give a feeling of 4 beats in a measure is to play the first one louder than the other 3. We get the effect of:

1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4

This style of emphasis is important because it lets the listener know that you are grouping things in four! If everything were the exact same there would be no real sense of the grouping. You would not be able to tell if things are grouped in 2’s, 3’s, 4’s or any other grouping!

Emphasis can happen in multiple ways, the easiest way to is just play the notes louder, but other ways are possible such as 4 note rising figures or other rhythms that bring out a particular grouping. This is how instruments that do not have much dynamic range, such as a harpsichord, imply a meter. Another option is the way articulation is used. Articulation is the particular way a note is played, such as more or less detached, or emphasized.

To be clear again, meter is our sense of how the grouping occurs! You may write it one way but if it doesn’t sound that way then you may have been better off using a different time signature so your meter and notation will match!

For example:

1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, ...

Here we see that even though we are counting to 4, like we would in 4/4, we are really emphasizing every 3rd number. Such a piece is really in 3/4, not 4/4. In this way you may write it one way but the meter does not care, it depends entirely on how it sounds. On this note, just because someone claims to be writing music in some time signature such as 7/4, doesn’t mean it is really “in 7/4". It could very well be in 4/4 and they are just writing with a 7/4 notation. Which would make the music hard to read for no good reason. The entire point of time signatures is to help you organize your meter in a way that is easy to read.

Fundamental Meter

Fundamental meter is the meter in which the first beat is emphasized and the others are not. It is the simplest meter implied by a time signature. For example:

2/4

1 2, 1 2, ...

3/4

1 2 3, 1 2 3, ...

6/8

1 2 3 4 5 6, 1 2 3 4 5 6, ...

All these cases use the fundamental meter the time signature suggests. However there are many alternatives. For example, 4/4 often emphasizes the first beat alot and the third beat slightly more than beats 2 and 4.

4/4

1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, ...

This type of emphasis is far more common than the 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4, ..., that the fundamental meter would imply.

Simple Meter and Compound Meter

Meters can be defined by two ways:

- How we group multiple beats together

- How we split up a single beat

Simple Meter

Simple and Compound meter refers to how we split up a single beat. If the beat splits into 2 parts then it is said to be simple.

An example is 4/4. In 4/4 the quarter note gets the beat. This beat splits into 2 8th notes. It could split further into 4 16th notes and continue splitting into 2 again and again. This is how we know it's a simple meter.

Another example is 3/4. Again the quarter note gets the beat and again it's splits into two. Following the same logic as before we see that it is a simple meter.

One more example, 3/8. Here the 8th note gets the beat, it can be split into two 16th’s, and this can be further split into 2. So for this reason it is a simple meter.

Compound Meter

Compound meter is when the beat splits into 3, and continues to be split into 3.

Here is where we break a little bit from our previous understanding of “the beat”. Consider 6/8. It has 6 8th notes and the 8th note gets the beat. We could view this from another angle, namely 3 8th notes make one dotted quarter. In this way the “beat” really goes to the dotted quarter, and the 8ths notes are a “splitting” of that. This breaks our prior convention from time signatures that says “the bottom number represents the note that gets the beat” and we will see this is the case for many meters like this such as 6/8, 9/8, ect…

This perspective shows that 6/8 can be viewed as a compound meter because the dotted quarter is split into 3. Split each 8th note into two 16ths and we find that 3 8th notes become six 16th notes! Another division of 3! This pattern holds as we divide it further showing that 6/8 can be viewed as a compound meter.

We could apply a similar analysis to 9/8 because 9/8 has 3 groups of 3 8th notes. We could again say this is like having 3 dotted quarter notes where the 8th notes are the splitting up of the dotted quarter note “beat”. Because we keep dividing by 3 we can say that this is a compound meter.

So to reiterate, if the beat splits into 2 continually then it is a simple meter, if it splits into 3 continually then it is a compound meter.

Perspective

6/8 is a bit strange because it can be viewed in two ways. First 6/8 could be split into two sets of 3 8th notes. We saw this lead to a compound meter. However, it could also be viewed as 3 sets of 2 8th notes. In this case it would then become a simple meter. There are other meters that also have this property and it is up to the way the music sounds to really determine if it's simple or compound. There are conventions however that can tip us off.

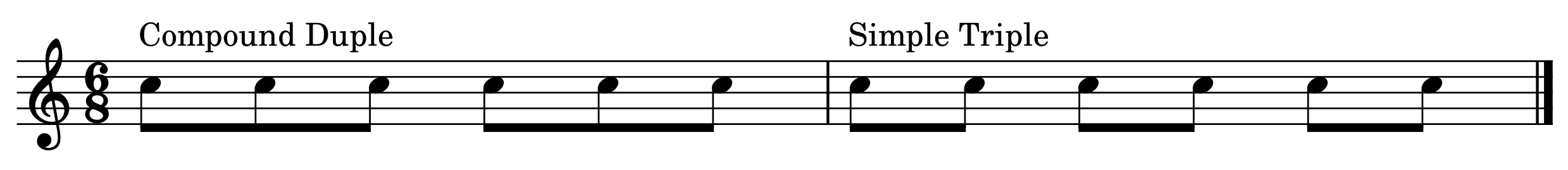

In 6/8 if the 8th notes are barred in pairs of 3 then it's implied that the desired meter is compound. If they are barred in pairs of 2 then it is implied that the meter is simple.

You may wonder now, why use 6/8 in "a simple meter" way when you could use 3/4. The answer is this:

In 3/4 you would count 1 2 3, 1 2 3

In 6/8 treated in "a simple meter way" it sort of forces the subdivision onto the rhythm, and it also tends to push the first of the 2 8th notes more, otherwise you might as well use 3/4. For example:

1 2 3 4 5 6, ...

When you start writing a piece of music you should pick a time signature that fits the meter you wish to convey.

Duple, Triple, Quadruple

How beats are grouped forms the second part of meter. If the measure is composed of 2 “beats” then it is said to be duple, if it is composed of 3 it is said to be triple and 4 beats is said to be quadruple. This can be extended to however many beats we need but it’s that easy.

The secret to naming a meter is:

- Identify the beat

- Identify simple or compound (this always comes first in the name of the meter)

- Identify how many beats form a measure

Examples

Example 1

For example, say we have 3/4.

- Quarter note gets the beat

- It is therefore simple meter

- There are 3 beats in a measure so it is triple

This leads to the conclusion that it is simple triple meter.

Example 2

Consider 9/8

- Dotted Quarter Note gets the beat

- It is therefore compound meter

- There are 3 beats in a measure so it is triple (our old understanding says there are 9 if we use the 9 notes but remember we identified the beats as the dotted quarter note)

Therefore 9/8 is compound triple.

Notes about 6/8

If we instead had 6/8 it would be compound duple if we go with the grouping of 3. 6/8 could also be seen as simple triple.In class it will be assumed to be compound duple unless the music suggests otherwise.

Notes about 3/8

If we go down to 3/8 this again could be seen as simple triple or compound single. (I’ve never seen it interpreted this way but it is possible. I am unsure if single is the right term for one beat in a measure.)

Final notes on identifying meter

So you can see it is pretty easy to identify a meter simply by looking at it. Hearing the meter is an entire other ordeal that is learned through a lot of playing songs and listening critically to music. For now we just want to understand the meter and how it relates to time signatures so that if someone tells you “you're not really in 7/4” despite you using that time signature you now know what they mean and why you might consider picking a time signature that fits your actual meter better.

Complex Meter

Meters that are actually combinations of multiple meters are called complex meters. They are used to simplify music notation that constantly switches between two meters. For example, say you have a phrase that goes from 2/4 in one measure to 3/4 in the next over and over and over. It may be easier to instead of writing a new time signature every measure (and I’ve played plenty of music that does this) to instead write it in 5/4 and then at the top of the music write 2+3, meaning it should be interpreted as 2/4 + 3/4. This makes it so you don’t have to write so much on the page.

5/4 of itself could be seen as simple quintuple meter, but it's hardly used for this purpose. It’s mostly used as a complex meter, at least in my experience that is why it's usually used.

There are plenty of other complex meters but you can see them as just combinations of multiple smaller meters if there is a specification at the top. For example say we are in 7/4 and it says 2+2+3 at the top. This means each measure should be seen as 2/4 + 2/4 + 3/4. It could easily have said 2+3+2 instead and that would be interpreted as 2/4 + 3/4 + 2/4. If there is no specification then it is either not a complex meter and should be seen as a simple septuple meter, or the barring and phrasing will make it obvious.

To support this series please consider donating via

paypalor joining the

patreon.